|

Lost Cantos of the Ouroboros Caves by Maggie Schein. Forward by Pat Conroy. |

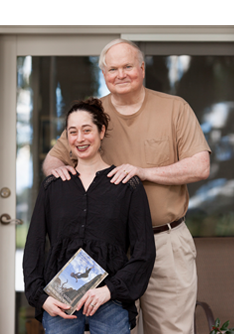

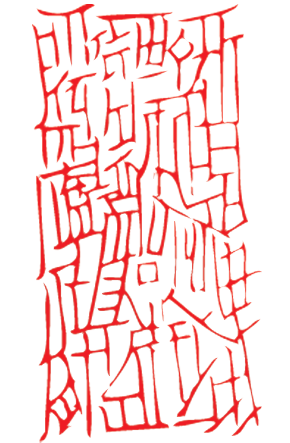

I met Maggie Schein on the day of her birth. I was present in the waiting room as her mother Martha went into labor with her klutzy, unhelpful father, Bernie, in feckless attendance. Bernie and I had become best friends in Beaufort High School and that friendship continues until this day. One of the luckiest things about that connection is I got to watch Maggie grow up in all her eccentric magic. Maggie never dressed like other little girls—I was raising three of them down the street, myself. Though she always dressed herself with style and attitude, it was a difficult ensemble to classify. She dressed in materials that looked like they were gathered from dempster-dumpsters located outside of gypsy camps or a wardrobe that fell off a train carrying a traveling circus. There was always a brazenness and comedy in her approach to the world—although I would’ve strangled her with great cheer when, at age eight, she put her new tarantula on my head and let it walk along the center of my face, pausing only to fiddle with my nose hairs. Though she had a dog and a few cats, Maggie’s heart belonged to her tarantula. From an early age, Maggie Schein was precocious in strange ways that portended a wild-eyed curiosity and an easy association with genius. But it was not language that held her full attention: She first fell in love with the grace, and the cunning, and the suppleness of the dance. For 12 years she gave up her life for ballet, that stern apprenticeship. I saw a dozen of her dance performances with a pre-professional company in Atlanta, but missed her during the New York years. She made her body lithe and hard as she joined the Feld Ballet/NY and then Hartford Ballet. The phrase “corps de ballet” has always served as one of the most beautiful groupings of words, and Maggie was on her way up when she sustained a career-ending injury, which also just happened to coincide with a deepening bent in her mind for studying philosophy. Like all ex-ballerinas, the future became a curious-yet-terrifying opportunity for her. She knew she didn’t wish to participate in that fate of most ballerinas—opening up a small studio with pretty boys and girls struggling at the barre, illuminated by great mirrors that could reflect the present, but had no idea about what the future may hold. And so she dove into the world of academia first at New York University and, then at the Unversity of Chicago’s famous Committee on Social Thought, where, when I asked if she missed dancing, she said she “learned how thoughts have a music, a rhythm of their own and words can be aligned together and articulated to create the shapes that move to those rhythms, so in some way,” she told me, “I am still dancing.” She studied with the esteemed South African writer, J.M. Coetzee, who would later win the Nobel Prize. It was there, in Chicago, that she met, conferenced with, and partied with some of the great minds of our times. After writing her dissertation on naturalistic ethics and receiving her PhD, Maggie found herself washed up on the shore with word fragments all around her in tide pools and sand drifts and nautilus shells. She found words calling to her from the air and from the sea and she made two fists of sand on the beach, and cascades of words fell beside her. Maggie was taken prisoner. The language had seized and held her in a grip that would not loosen. Maggie came to me when she had something to show that she’d written. You trust the guys and the girls who are there when you are born. First of all, I found myself dazzled by the utter, plain-song beauty of her prose. I’ve always been one of those readers ensnared by the bright flow of language and the masters who can hurl that language into the air to make new galaxies for a tired-out sky. Instantly, I knew I’d discovered a grandmaster with Maggie and her book flew me out toward the great books where ideas were as original as the words themselves. Once in Rome, I met the great Italian fabulist, Italo Cal-vino, at a coffee bar after I had recently finished his book, Invisi-ble Cities. My first impulse was to drop to my knees and kiss his ring, but he seemed much too shy to endure such an outrageous gesture. I’ve mentioned my admiration of Calvino to all of my friends and many have fallen in love with his work, but many also despise him. Because Calvino writes with such breathtaking subtlety, he’s not understood by the literalists of this world. Robert Jordan and I both graduated from The Citadel and I never realized the enormous power of his series of books called “The Wheel of Time” until after his death. A friend reommended—no, she forced upon me—the works of George R.R. Martin, and these writers set up in my cotillion bells of memory my first glorious encounters with Stephen King, Edgar Alan Poe, Anne Rice, and the great Tolkien himself. When I open a book, I command that the writer turns me inside out, earns my respect with ideas and encounters I’ve never dreamed of or imagined in my most crestfallen nightmares. In 1982, when I was living in Rome, the novelist Jonathan Carroll sent me his first novel. It was called the Land of Laughs and I was enjoying it with pleasure when two dogs began talking to each other. That stopped me in mid-sentence, but the book had already grabbed me by the collar, I finished it and called Jonathan right away to tell him how much I loved his novel. Now, I’ve been reading Jonathan Carroll for thirty years and his work is strange, hallucinatory, and necessary. He opened my mind to fictional worlds I had never traversed and my life’s been richer for it. Recently, he sent me a copy of his collected short stories and there’s the sweetness of magic on every page. Though Maggie Schein calls her stories “fables” I’m not convinced that’s an accurate title. But because Maggie went to The University of Chicago and I went to The Citadel, she is a lot smarter than I am and wins every argument with me. Maggie Schein has written an oddball, perverse work of genius. Her fables are a genuine seeker’s attempts to bring order to the world, to subdue chaos, to establish laws among tribes that are brand-new to language. Omens abound and Eagles scream truths from a thousand feet and every line is a poem that brings order to a restless universe. She writes a sentence like a string of black pearls and I believe a cult is about to form to track her future path as an artist. She won’t give you a single thing of what you want, but she’ll give you a lot more. Her Can-tos seem enchanted to me, as if they were some secret language found on the rear ceilings or the walls of Lascaux. Her realm is timeless and enchanted and braided together with all the power and seduction of myth herself. Maggie Schein writes like a fallen angel, and I was there on the night of her birth. - Pat Conroy, August 2012 |

"Maggie Schein is gifted. Her novel is so vividly imagined, so rich and evocative, so beautifully written, you'll find yourself holding your breath in parts. I highly recommend this book."

- Judy Goldman, author of Losing My Sister: A Memoir    |

| Copyright © 2012 Maggie Schein. All rights reserved. | Haven | Lost Cantos | The Temple | Acquire | Connect | Creator | Words |